My father died before I was born, and then showed up in my life eleven years later. I learned of that day through stories and newspaper articles. If a person wanted to know about that day, it wasn’t difficult to find information. It was the most famed event in our small town of Frog Pond. News papers all over the south ran stories about it from Thanksgiving to New Years. Local papers ran it right next to the discovery of King Tut’s tomb, and the election of the first female U.S. Senator.

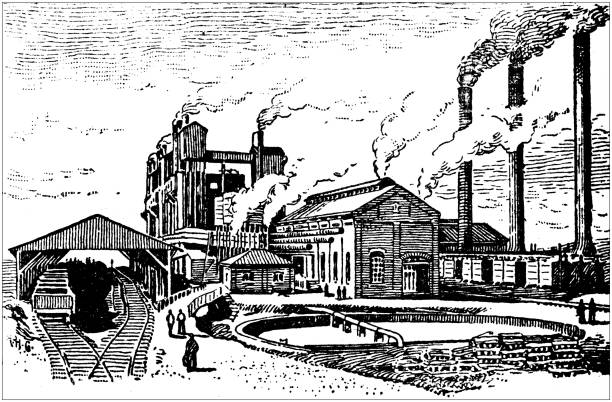

That day there was a thick gray haze in the air, common to any mining town. It was hard to distinguish at times between when the sun went down and when it came up again. Every surface was covered with a thick and deathly dust. My mother packed my father’s lunch in a metal box, and waited for him to get dressed, drink his coffee and leave. She would follow him out to the front yard, hand him his lunch and kiss him on the cheek.

“See you in a little bit,” he said. According to my mother, it was always the same words of departure. See you in a little bit. There was an expectation that at the end of my father’s shift, my mother would be woken by the creaking sound of the front screen door.

Some mornings my father would drive to work, other times he would walk. Our home, which was no bigger than a match box, and sat three miles from the number three mine where he worked. On this day, he decided to walk. I have walked the same route many times. I would imagine that I was matching him step for step. He passed two churches. The baptist church on his right and the Methodist church on his left. Both congregations shared a cemetery. I guess when you’re dead it doesn’t really matter if you were baptized as a baby or not. All that matters is that the water knocked the sin out of you. Truth be told, the town was not big enough to have more than one cemetery.

A small distance from the methobaptist cemetery was the number three mine. Every abled body man in Frog Pound and some neighboring towns worked at the mine. Coal dust was just as much in our veins as it was in the air we breathed. Most boys never finished school, because there was mining to do. My father on the other hand was perhaps the only man underground with more than a fifth grade education. He could read and write. He was not a native to Frog Pond, and if you asked anyone who knew him, he made that abundantly known wherever he went. He volunteered to read the scripture every Sunday. He could have done anything. He could have been anyone. For some reason, unknown to anyone still living, he chose to be a miner.

Had it not been for the events of this day I myself, after completing grammar school, I would ‘ve started digging. I happened to like school. I started reading at a very young age. I owe this to my mother. She insisted that I learn, and worked tirelessly to teach me the craft. I read everything from the grocery list, to the book of John. This left a conflicting feeling in my gut. I lost my father on this day, but I escaped coal. My father gave his life for my own.

On his way underground, my father would have passed a sign that displayed the quota of the day. Coal miners and police officers had one thing in common, and I mean only one thing, the more they put in the wagon, the better off they were. The boss men at number three were aiming for a record day. “52,000 tonnage for November!,” the sign read. This would have been the second month in a row that number three would have broken a record, and the powers that be wanted it more than a squirrel wants a nut. My father was one of four hundred and seventy five men who would bathe in black soot to give the fat rodents their nuts.

Coal was transported from the seam to the surface in carts that were moved by an electric cable system. One car at a time, in groups of three. No one knows exactly what went wrong, but carts at the surface of the mine became jammed. The operators tried to jerk them free, but the force was too much for the cables and the carts began their descent back to the pit from which they came. A dark descent. All anyone at the surface could do was watch.. and wait. The large steel boxes barreled toward the bottom of the slope. A metallic hum trailing down the pit. Newton once said that an object in motion will stay in motion unless something stronger stands in its way. At the bottom of the track, three very full containers were waiting to make their ascent, that is until their rogue companions crashed into them. Newton was right.

A cloud of smoke filled the cavern. One of the cables to the electric carts snapped and a spark kissed the dust. It happened so fast, no one had time to even jump from the fright. The explosion roared and the next thing they knew they were trapped in blackness. A dark confinement. The explosion was felt nine miles away in Birmingham, and it was said that the smoke could be seen in Montgomery. I don’t know if that last part is true. Those that survived said that it knocked them clear off their feet.

“I had never heard or felt a thing like it,” Roger Mule said. “One minute I was loading a cart, and the next I was picking coal out of my skin and hacking dust out of my chest.” Mr. Mule’s story was one of a few that was told in the newspapers in the following weeks.

“The good Lord saved me.” He fought back tears. That isn’t something you saw much of in Frog Pond, a grown man crying.

“God himself got me out of that mine.” Mr. Mule was known for smoking a corn cob pipe. I can see him now, speaking these words out of one side of his mouth as the other side held his pipe between his teeth.

The entire town rushed to the scene. Only a few people had an automobile. My fathers truck sat in our front yard. Mother didn’t know how to drive, but she learned that day.

When she arrived at the mine, everyone was sitting on pins waiting to see if their husband, son, or grandson would be the next body to either walk out, or be pulled out. Most of those pulled out were covered by a shirt, coat, or blanket if one was available. They were dead. Dread, grief, or thankfulness. Some said that they felt all three at once, or two at a time. Joy was absent. Joy would come later, but not for all. Joy was only possible when the dust settled and for the first time in modern memory, the sun was bright in Frog Pond. My mother felt dread and grief, sometimes simultaneously, sometimes separately. She never felt joy. My father neither walked out, nor was he pulled out.

“Ma’m, it’s getting dark. Why don’t we get you home,” Earl Watson said to her. Earl owned the hardware store in town. He was one of the few men who didn’t dig for a living. He’d much rather sell the shovels.

“I can’t. Not until Thomas is found.” her eyes were fixed on the opening of the mine.

“Elenore, they will find him. Have faith.” He placed a hand on her shoulder.

Mother stood there cradling her face with her hands, sobbing, watering the black ground with her tears. She overheard some men talking about returning the next day to continue looking for survivors. Every day she would return with them. She would follow the same routine that her and my father had always done. She packed a lunch, walked outside, and when she got in the yard she would whisper to herself, “See you in a little bit.” Some days she would drive. Other days she would walk and pass by the Methodist church on her left and the Baptist church on her right. She would wait, until one day there was nothing to wait for. The mine closed and my father’s body was presumably dead and buried somewhere, hundreds of feet below the surface.He was never found. Earl was wrong.

The day after the mine closed my mother found out that she was pregnant. In all the different times, and different versions of the stories I have heard about this day not once was I told that my mother felt dread or grief that day. Finally, joy came in the morning. There would be time for dread, and I am sure there was. Though she would have never told me, life in Frog Pond would not have been easy for a widow, much less a widow with a baby.

She rubbed her belly, “See you in a little bit.” I was named after my father, Thomas Watson Sanders.

Leave a comment