I hadn’t stepped foot in my father’s workshop for more than twenty years. I told myself it was complicated. It never really was. The passing of time has a funny way of kicking you right in the teeth. We only realize things weren’t that complicated once it’s too late to fix them.

I stand outside the red building in the backyard of his house for what feels like another twenty years. I call it his house because it stopped being my home a long time ago. The building was red once, but now it’s a dull rust color, with patches of green moss creeping across the wooden siding.

The door creaks and groans as I open it. The room smells like sawdust and wood stain. Dust floats in the air, passing through columns of light from the windows. It’s quiet, almost peaceful, but empty. Empty of the person who gave it purpose. I realize that me and the workshop are one and the same, orphaned, left behind, empty.

A workbench stretches along the back wall. Tools are scattered across its surface, as if someone left them there with every intention of using them again.

“He’s not coming back,” I whisper, picking up a chisel.

I consider hanging it on the wall, where it belongs. In the end, I lay it gently back down.

Everything in the room is just as I remembered it. I half expect my father to walk in, hunched over, cane in one hand, and mutter, “Are we ever going to finish that darn clock?”

But he’s gone.

And the clock is nowhere to be seen.

I start walking around, taking stock. Soon I’ll have to decide what to do with all of it. I pull out my phone and open a note:

circular saw… sale.

screwdrivers and chisel set… sale.

hammers… sale.

No sense keeping any of it. I don’t have the room. In the corner are a few boxes, probably more tools or magazines. He never threw anything away, just moved it out here, in case he needed it one day.

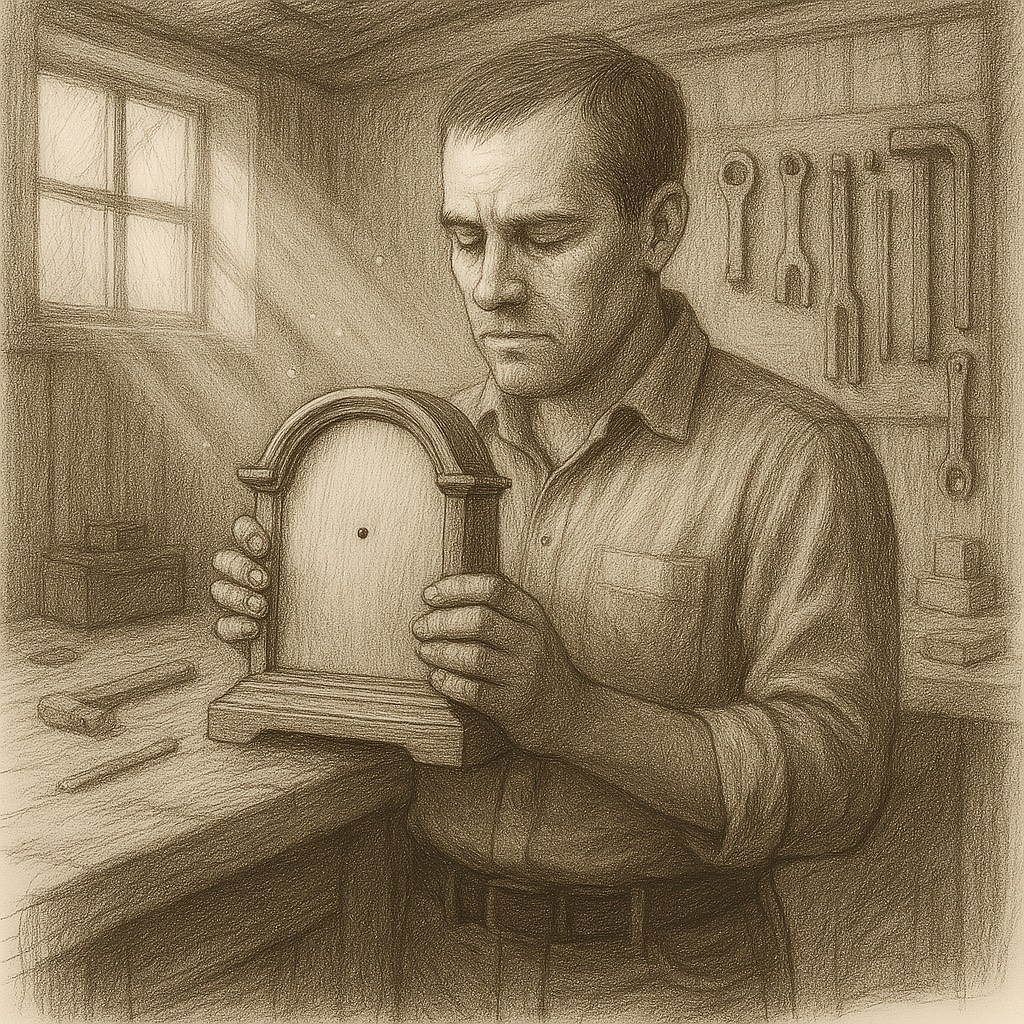

I’m on the third box, maybe the fourth, when I find something wrapped in a blanket. It’s solid. I lift it out and place it on the workbench, then carefully unwrap the fabric.

The face of the clock is blank. No numbers. No hands. The cedar wood is smooth, untouched by stain or varnish. I remember the night we started it. He’d ordered a gear kit online and carved the casing from a block of cedar. I sat on a stool and watched him chip away at the wood until he was satisfied with the shape. Occasionally, he’d let me try, but what he really needed was my help with the gears. Parkinson’s hadn’t fully stolen his ability to work the chisels yet, but he couldn’t hold the tiny screws needed to assemble the clock’s movement.

Now and then, he’d give me a nod, his quiet way of saying I was doing something right. Other times he’d mutter, “Ain’t it ironic we’re building a clock? At the rate you’re going, we’ll run out of time before we finish it.”

It wasn’t ironic at all.

I turn the piece over in my hands, trying to see how far he got. On the bottom of the clock, in shaky ink, are the words:

“To be completed with my son.”

I bring the clock to my face. Tears soak into the bare wood. The dust swirls in the rise and fall of my chest. I gave up a long time ago, but he hadn’t. He waited. He watched time pass too quickly. Watched dust settle too thickly. Until, eventually, time ran out, and the dust buried him.

I take out my phone and open the list again:

circular saw… keep.

screwdrivers and chisel set… keep.

hammers… keep.

“Dad,” I whisper, “let’s finish the darn clock.”

Leave a comment