I sat in Sunday school and listened to my teacher talk about Jesus. Mrs. Rockner was reading to us from John 19:27, “Then saith he to the disciple, Behold thy mother! And from that hour that disciple took her unto his own home.” I raised my hand and she called on me to ask my question.

“Did Jesus have a father?”, I asked. This was very out of character for me. I rarely ever spoke unless I was spoken to, and never asked questions in fear that I was asking the wrong one.

“He was the son of God, doofus”, one of the boys in the back of the room shouted.

The room erupted in laughter and had my tie not been a clip on I would have choked from the knot that formed in my throat. Mrs. Rockner raised one boney finger to her mouth and shushed the class.

“We will not call anyone a doofus in God’s house”, she said behind her clenched teeth. “Tommy”, she called out to me. “Tommy, Joseph was Jesus’ father, but the Bible doesn’t speak a lot about him. It is possible that Jesus grew up without a father.” She grinned at me. She knew why I was asking. I raised my hand again.

“Yes, Tommy?”

“So Mary was a single mom? She took care of Jesus all on her own until he was a grown up?”

“I guess you could say that.” She answered, her eyes peering at me over the rim of her glasses. She cleared her throat and continued to teach the class. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. We came to this building three times a week, twice on Sundays, to talk about him, sing songs about him, we even talked to him, and he was raised by a single mom. Jesus was an important person, and Jesus didn’t have a father.

A boy in my class raised his hand, and Mrs. Rockner called on him.

“Wasn’t God the father of Jesus?”

Mrs. Rockner shook her head in approval. “He was indeed, but I think Danny was curious if Jesus had an earthly father. Isn’t that right Danny?”

I nodded my head, but kept it hanging below my shoulders.

“God is everyone’s heavenly father if they believe in Jesus”, Mrs. Rockner said.

I wasn’t sure what she meant by “believing in Jesus” but, if believing in Jesus meant I could have a father, and Jesus was raised by a single mother I wanted to believe in Jesus. I raised my hand again.

“I believe in Jesus because he was raised by a single mother.” I could hear tiny whispers travel through the room. Several of my classmates were talking in each other’s ears and covering their mouths with their hands. I knew they were talking about me. They were always talking about me. They were always waiting for me to ask a stupid question, or say something strange. I was different. In fact, I was more like Jesus than any of them. All of them had fathers. I sat there, pinching the skin of my left index finger. I did this when I was nervous. Mrs. Rockner was facing the chalkboard writing our memory verse for the week. She smiled at me, the whispers stopped.

“And will be a Father unto you, and ye shall be my sons and daughters, saith the Lord Almighty.”

“Tommy, I think that is a great thing. A really great thing,” she said, turning from the chalkboard.

Sunday school always ended promptly when it was time for it to. Usually Mrs. Rockner would escort us all to the church house so that we could sit with our parents. Well, in my case it’s just one parent. This particular Sunday, Mrs. Rockner asked me to stay behind and sent everyone else out of the classroom.

“Tommy, would you mind staying back with me for a moment?” Without protest, I obliged to her request. This was a welcomed reprieve from the quiet insults thrown at me like tomatoes from the other kids in my class.

“Yes, Mrs. Rocker.” I said, walking toward the small desk that sat in the back of the room. She patted the seat of a chair next to the desk, signaling for me to sit down.

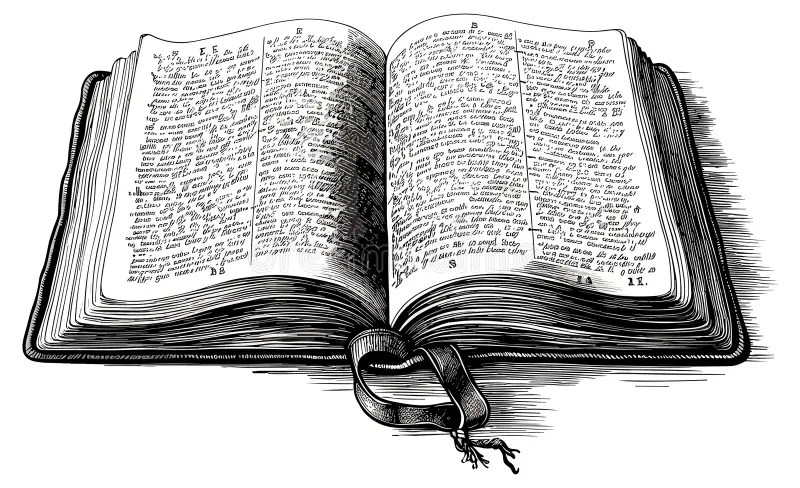

She always carried a large bag with an embroidered cat on the front of it. I haven’t a clue what she carried in it, or why a person would need something the equivalent size of a suitcase with them at all times. Regardless, after I agreed to her request she started to dig into her bag, looking for something. The bag with its wide mouth appeared to be swallowing her whole until finally she emerged with a leather bound book.

“Sorry, I keep my life in the bag. Sometimes things hide from me.” She blew a piece of hair out of her face, and took a deep breath.

“Thomas, I have noticed that you ask a lot of questions. Sometimes they are questions that are difficult for Mrs.Rockner to answer. You are a very inquisitive young man.” My face scrunched and my head tilted to the side when she said this.

“What I mean is that you want to know a lot about things.” She placed the leatherbound book on the table in front of me. On the front cover, in gold inlaid letters was my name. Thomas Watson Sanders.

She placed her hand on the book and looked at me. “Tommy, this is a Bible. Not only is this the Bible, but it is your Bible. See, it has your name on it.” She pointed to the gold letters. The book was worn, and the leather was dry and cracked. The edges of the cover were starting to tear. The gold gilding had long worn off, some of it was still visible though dull. I had never seen a book like it. Two columns of words on each page.The front of the book had a page for a person to put there name, births and deaths of family members, and even a place for marriages. On the page for the owners name, written in blue ink,

Presented to: Thomas Watson Sanders

With Love. Your Wife, Elenore.

This was his. Held held it in his hands. I stared for what seemed like an eternity, running my fingers over his name, imagining what these pages would tell me if they could talk. I flipped page after page to find notes in his handwriting. This was the closest I had ever been to my father, and for just a moment time stood still.

“Years ago I found this while going through some old books in the church,” she placed a hand on mine. “He must have left it here the Sunday before the accident.”

I cried. I am not sure why it cried. I never grieved his death because I never knew him. How does a person miss something that they never had? I am certain that the feeling that I felt in that moment was grief, because for the first time my father became a real person to me, not some fantasy in stories, but a real person. I sucked up a wad of snot and gathered myself so that I could speak.

“Did you know him?” I asked.

“Oh yes, I knew him very well,” She said. “Would you like for me to tell you about him.”

“Yes, very much so.”